Hearing Mark's Gospel

- Dec 6, 2017

- 6 min read

During Advent, I will be featuring three guest posts, each by a different author and with a different theme and style. This week features an academic look at the Gospel of Mark. (If you read the post on the Revised Common Lectionary a few weeks ago, you may remember that we are just beginning Year B, which features the Gospel of Mark.)

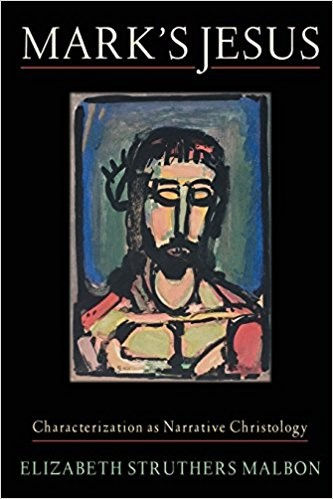

This guest post is written by Dr. Elizabeth Struthers Malbon, Professor Emerita of Religion and Culture, Virginia Tech. Dr. Malbon, who is also my mother, is known nationally and internationally for her literary studies of the Gospel of Mark. She has authored five books, coedited five books, and written and edited numerous articles. Dr. Malbon is an active member of the Society of Biblical Literature and the Society for New Testament Study.

Grace and peace,

Annemarie

Mark’s Gospel was probably the first to be written, toward the end of the first century. No author claims it within the text, but by the second century it had received the name “According to Mark”—and later “The Gospel according to Mark.” Its author was probably the first to collect together stories of and about Jesus that had been passed down orally for a generation and put them into writing. But what was written was written to be heard by an audience, not read silently and privately.

The Gospel of Mark is not contemporary—it is ancient. Because readers continue to find Mark relevant, we sometimes forget that it was written in Greek, somewhere in the ancient Mediterranean world, perhaps not long after the year 70 of the Common Era. That was the year of the destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans, and many interpreters suggest that Mark’s Gospel was written in response to that devastating event. Before this first-century text can speak to our world, we must listen to its world. That world was an oral world—a world of anonymous storytellers and live audiences. We follow ancient tradition in calling this gospel “Mark,” and we might also follow the lead of its teller in finding the story more important than the storyteller.

For most of its life, the Gospel of Mark has played second fiddle to the Gospel of Matthew, which used Mark’ Gospel as a source. Mark’s Gospel was thought to be abrupt and choppy. In the past generation or two of scholars, the author of Mark has come to be appreciated more fully for the way he positioned the stories he collected and what he added to bring them together as “the beginning of the good news” (1:1). Mark’s literary style (or rhetoric) is one of juxtaposition, of placing one element or incident or story next to (or sometimes in the middle of) another element, incident, or story—with the implication that the audience will participate in the hearing of the story by way of interpreting the significance of the juxtaposition. The rhetoric of juxtaposition is thus a rhetoric of involvement and implication. Mark’s Gospel assumes an engaged audience. When you hear or read a passage in a new light because you become aware of how it is juxtaposed with another passage that you heard or read just before it, I believe you are hearing Mark’s Gospel in the way the author expected, or at least hoped for.

Mark still strikes some readers as incomplete. Lectionary readings for Year B, beginning on the first Sunday of Advent, are sometimes drawn from other Gospels because Mark has no “Christmas story”—neither shepherds (Luke) nor kings (Matthew). In addition, the “Easter story” in Mark (16:1-8) is stark—so challenging to hear that early interpreters made additions to it (16:9-20). Yet Year B challenges us to read, hear, and preach Mark’s Gospel on its own terms, listening to the force of Mark’s voice without harmonizing it with the other Gospels.

The Gospel of Mark is not intended to be an objective account of the historical Jesus; it is subjective, told from faith to faith. Nor is Mark’s Gospel a collection of theological affirmations about Jesus as the Christ. Mark is a gospel, good news of and about Jesus, told by the persuaded to be persuasive. And Mark is a story—a continuous narrative with settings, characters, plot, and rhetoric—a story with rich theological dimensions but in the form most frequent in the entire Bible—the story of God’s people in conversation with God and those who speak for God. Here the challenge of Year B is to keep this story going within a congregation through interruptions from other Gospels and disjunctions in the lectionary readings from Mark.

After the initial story of Jesus’ baptism by John in the Jordan River, Mark returns the story to Galilee for most of the first eight chapters. In Galilee, Jesus’ home region, Jesus proclaims that the kingdom (or reign) of God is breaking into history, and Jesus’ powerful words and deeds, his teaching and healing, illustrate God’s power. From the middle of chapter 8 through chapter 10, the Markan Jesus, with his disciples, is on the way, on the way from Galilee to Jerusalem where he will suffer at the hands of men. Along the way, Jesus is trying to teach his disciples that the way of discipleship is the way of service to the powerless and, if necessary, suffering at the hands of the powerful. Chapters 11-16 recount the passion story, the story of Jesus’ suffering and death at the hands of the officials of the Roman Empire. Mark’s Gospel has been called a passion story with a long introduction. Mark’s Gospel ends abruptly, although additional endings were added later to soften the force of its ending.

One key term that can serve to highlight both form and content central to Mark’s story is juxtaposition. Mark’s Gospel is not known for smooth transitions but for dramatic contrasts in which settings jump from the synagogue to the sea, responses to Jesus shift between adulation and antagonism (with a good measure of misunderstanding), and actions follow actions “immediately” with few connections and little commentary. Narrative settings juxtapose Galilee, the scene of Jesus’ deeds of power and strangely authoritative teaching, with Jerusalem, the scene of Jesus’ passion. Settings juxtapose the private and secular “house” with the public and religious “synagogue” and “Temple.”

Character interaction juxtaposes three levels of conflict. The first is the foundational but background cosmic struggle of God and Satan—and their respective representatives, Jesus and the demons and unclean spirits. The second level of conflict is the middle-ground conflict of authority between Jesus and the political, social, and religious establishment. It is important to avoid the anachronistic—and even dangerous—reading of the conflict between the Jewish authorities and the Jewish Jesus as a conflict between “Judaism” and “Christianity.” Rather the juxtaposition portrays a prophetic conflict between practitioners and authorities that recurs in all religious and cultural traditions. The third level of conflict is the often foregrounded human struggle for understanding between Jesus and his followers, both the twelve and a larger group of followers. The Markan storyteller portrays the disciples as struggling learners, a model for the audience, as it were, to teach the audience what it means to follow this Jesus who proclaims and enacts the in-breaking of the rule (kingdom) of God.

The plot juxtaposes deeds of power and authoritative teaching that bring God’s rule in the present age with service to the oppressed and suffering at the hands of the oppressors, deeds that challenge traditional understandings of power and authority. The Markan audience is challenged to hear these juxtapositions meaningfully: to consider the varied responses to Jesus in light of each other, to ponder Jesus’ proclamation of God’s rule in light of the status quo it challenges. Mark’s Gospel offers no answers for passive readers but engages the audience in Jesus’ struggle to understand and do the will of God and the disciples’ struggle to understand and follow Jesus.

Mark’s Gospel juxtaposes ways of understanding and acting with exousia, a Greek word that can be translated “power” or “authority.” Mark’s Jesus teaches with “authority” (1:2) and announces that his followers will see “the kingdom of God . . . come with power” (9:1), but not the authority of the traditional religious leaders of his day nor the power of the dominating political power of his day, the Roman empire. To hear Mark’s Gospel in this lectionary Year B is to juxtapose this story of Jesus with our own stories as latter-day followers, rejoicing in the blessings of the rule of God in the present age but also living with the challenges of the transition to the new age, challenges that put us at odds with the status quo when we insist, as Mark’s Jesus does (10:45), on serving rather than being served.

Elizabeth Struthers Malbon

Professor Emerita of Religion and Culture, Virginia Tech

Using technology to increase access to youth mental health support may offer a practical way for young people to reach guidance, safe-spaces, and early help without feeling overwhelmed by traditional systems. Digital platforms, helplines, and apps could give them a chance to seek support privately, connect with trained listeners-orexplore resources that might ease their emotional load. This gentle shift toward tech-based support may encourage youth to open-up at their own pace, especially when in-person help feels too heavy to approach.

There is always a chance that these tools-quietly make support feel closer than before, creating moments where help appears just a tap away. Even a small digital interaction might bring a sense of comfort. And somewhere in that space, you…

Detailed and practical, this guide explains concrete rebar in a way that feels approachable without oversimplifying. The step by step clarity is especially useful for readers new to the subject. I recently came across a construction related explanation on https://hurenberlin.com that offered a similar level of clarity, and this article fits right in with that quality. Great شيخ روحاني resource. explanation feels practical for everyday rauhane users. I checked recommended tools on https://www.eljnoub.com

s3udy

q8yat

elso9

Really appreciate this content—it’s practical and easy to understand. I explored a wooden furniture wedding sale last week and found some stunning pieces that elevated the entire décor setup. Your tips make the selection process even smoother!

The range of Yellowstone Clothing For Women allows every fan to find a style that suits them, whether it's Beth's powerful looks or Monica's elegant style. Discover a vast array of options on the Western Jacket site.

good article